1869-1881

One morning last spring, while combing through a box of old menus, I stumbled across a lost chapter of American culinary history. There had been only a brief opportunity to examine the tattered contents of this box before purchasing it, and I was now sorting through the hodge-podge of papers more carefully, hoping to find a hidden gem, when it suddenly occurred to me that forty-five of the menus from New York might somehow be related to each other. As I separated these from the others, and arranged them in chronological order from 1869 to 1881, an intriguing narrative began to take shape, for it appeared they had once belonged to a hotel steward named Antonio Sivori. No longer remembered, Sivori was well-known in his day, catering some of the city’s most important social events.1, 2

Various bits of indirect evidence point to Sivori as one who originally saved these menus. In addition to one signature and various notations, his name appears on seventeen of the menus, showing him either as the proprietor, steward, or caterer. Some of the menus are fragments of the original, where only the bill of fare was retained as a record of the meal, not as a personal memento of the event. In addition, many of them still have remnants of tape indicating that they were torn out of the same scrapbook, probably many years ago.

It would not have been unusual for Sivori to maintain a scrapbook as a journal of his work. Such practices were common. Hotel stewards often set aside a menu from each dinner so that they could be hand-sewn into books—some were bound in full morocco leather, complete with marbled end papers and the steward’s name imprinted on the spine. Although a few of these record books have survived, the group of menus possibly saved by Sivori may be unique. The nomadic nature of his career yielded menus from a wide range of venues and activities, providing a rare glimpse of the working life of a caterer in the nineteenth century.

This trove of evidence also stands on its own, revealing the ethos of the social activity during a transitional decade in the city's history. Emerging from the chaos of the Civil War, New York developed a more ordered sense of community in the 1870s, and the new civic spirit was reflected by the themes of its banquets and balls. There were reunions of all kinds, where the citizenry reconnected after the turbulent years of the war. The leading members of society also held many charitable balls, raising money to help the poor caught in one of the worst depressions of the industrial era.

Sivori’s Restaurant (ca. 1870)

Born in Genoa in 1833, Antonio G. Sivori was educated for the priesthood, but decided not to take the orders and immigrated to the United States when he was fifteen years old. He landed his first job at Delmonico’s and later worked as a waiter for the Astor House, the Barrett House, and the Metropolitan Hotel. After becoming a U.S. citizen in 1857, he applied for a passport the following year, indicating that he may have returned to Italy during this period.3 Sivori served in the Union Army during the Civil War and by 1870, he was living near Washington Square with his wife and son. At about this time, he owned a small restaurant on Eighth Avenue, near 23rd Street, as shown by the à la carte menu below. Throughout his life, Sivori frequently changed jobs, working variously as a restaurateur, steward, caterer, and hotel manager.

St. James Hotel (1869-1872)

Seven menus, dating from 1869 to 1872, come from the St. James Hotel on Broadway at 26th Street. According to a popular guidebook, this fashionable hotel was a favorite haunt of the “better class of sporting men, especially those interested in the turf. Many theatrical stars have been patrons of the house.”4 The Friendly Sons of St. Patrick celebrated its 85th anniversary here on their saint’s religious feast day in 1869.

Ignited by the Great Famine of the 1840s, the Irish Diaspora to the United States was immortalized in the ballad, “The Green Fields of America.”

The numbers and dollar signs scrawled on this menu indicate that it was a working copy, seemingly used to calculate the cost of this banquet. Keeping in mind that these figures may not represent all of the costs, they add up to $158.60, representing about $2850 in today’s dollars, or $47 a cover. There is nothing written next to the decorative ornaments or simple desserts, perhaps indicating there were no significant costs associated with these accoutrements. Comparing the relative cost of the dishes is also revealing. At $18, the most expensive dish is larded sweetbreads with peas. Called the releve, this course was first presented to the diners, before being taken to a sideboard to be carved and plated. Next in line, two of the entrées cost $15 each—the filet of beef with mushrooms and capons with truffles; the lamb chops are only a third of that amount. On the opposite end of the spectrum are the raw oysters, devoured by Americans of all classes in the nineteenth century. On the East Coast, the wholesale price of choice oysters was two to three for a penny when purchased by the bushel. In 1870, three dollars could easily buy enough oysters to provide sixty diners with a dozen each.

|

| St. James Hotel, ca. 1870s |

The alumni of old Public School No. 7 on Chrystie Street held its second annual reunion on February 8, 1870. This menu was signed by Sivori on the back, indicating that it was once in his possession.

Two weeks later, the well-to-do alumni of Williams College convened at the St. James for their reunion on George Washington’s birthday, incorrectly noted on the menu below as the birthday of founder Ephraim Williams. The illustration on the back shows the monument they erected in memory of classmates killed in the Civil War.

Evoking the convivial spirit of the era, the menu below reveals a brief, but joyous moment in the history of Broadway theater. This supper was called the “Saratoga Centennial,” celebrating the hundredth performance of Saratoga; or, Pistols for Seven in March 1871. This wildly-popular romantic comedy was performed at the Fifth Avenue Theatre on West 24th Street, near the intersection of Broadway and Fifth Avenue at Madison Square, only two blocks from the St. James. Closing after 101 performances (then regarded as a very good run), Saratoga was one of the first American plays to become internationally successful.

Comprising mostly cold dishes, this late supper was probably served for the theater company after their last Saturday performance. Several desserts are named in honor of the young leading ladies—charlotte à la Linda Dietz, blanc mange à la Clara Morris, and punch à la (Fanny) Davenport. The ice cream refers to the character “Effie Remington,” the lovely belle played by Davenport in one of her most memorable roles.

|

| Cigar Box Label, ca. 1870s |

An arts journal named The Aldine hosted its annual dinner at the St. James in March 1871. The following month, this periodical published writer Mark Twain’s “Autobiography,” which read in full: “I was born November 30, 1835. I continue to live, just the same.”

At The Aldine banquet in February 1872, Twain gave an after-dinner speech that reportedly brought the house down, producing howls of laughter. Charmingly illustrated, the menu below features an entrée called “scrapple à la Philadelphia,” an unusual dish for an upscale literary gathering in New York.

Sinclair House - Academy of Music (1871)

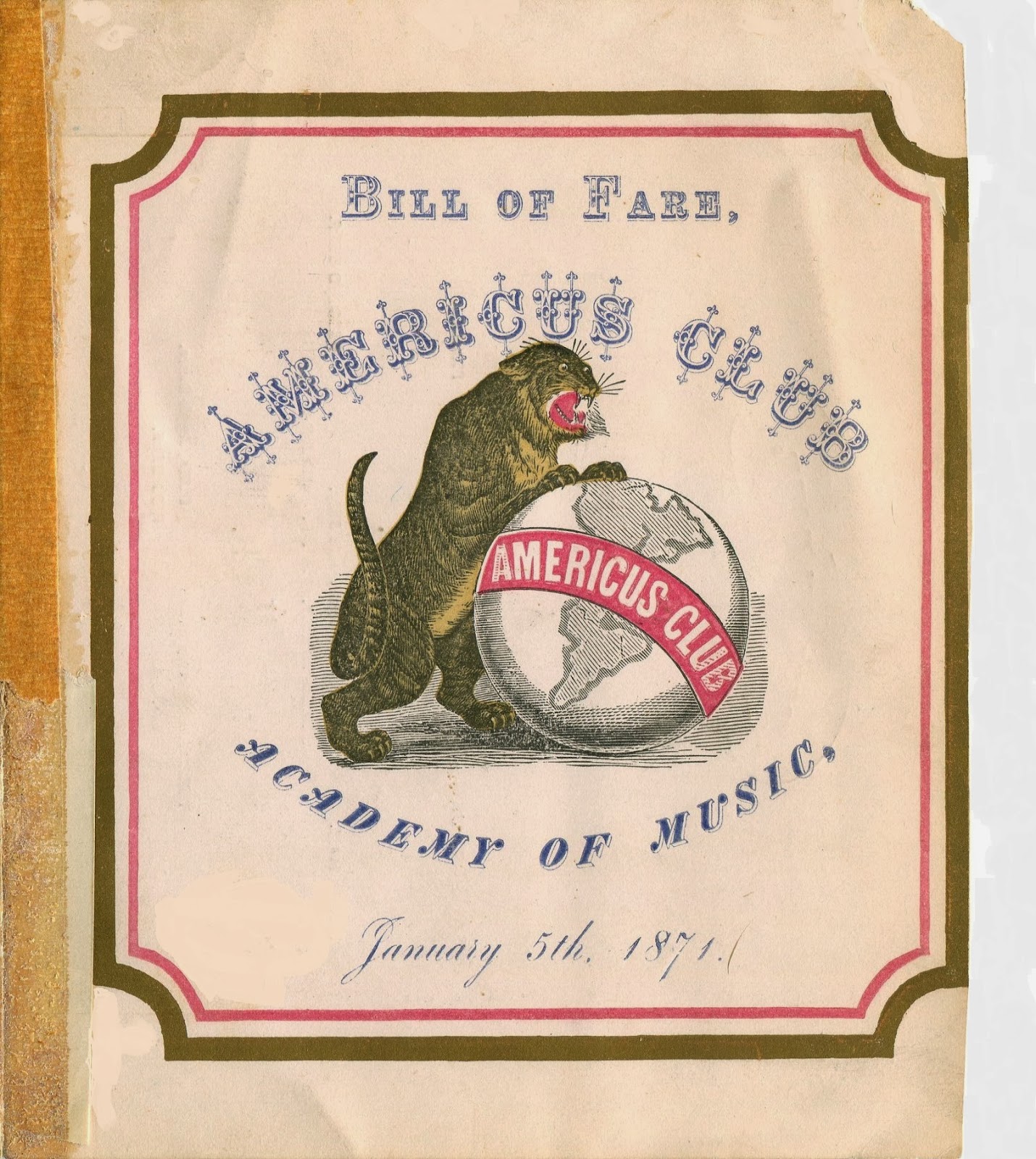

William “Boss” Tweed, corrupt leader of the Democratic Party's political machine called Tammany Hall, was riding high at the beginning of 1871. In addition to being the city’s third-largest landowner, he was a director of the Erie Railroad, the Tenth National Bank, and the New York Printing Company, as well as proprietor of the Metropolitan Hotel. Tweed was also the president of a political organization called the Americus Club (originally Volunteer Engine Company No. 6) that held a ball in January of that year at the Academy of Music, spilling over into nearby Irving Hall. Although he and his cronies had been siphoning off the city’s wealth for years, Tweed became a national celebrity when some of his most outrageous shenanigans came to light, such as when the new courthouse ended up costing twice as much as the United States paid for Alaska. Newspapers across the country ran articles about his large party in New York.

The symbol of Tweed’s political machine was the “Tammany Tiger,” illustrated on the front cover below, ferociously clawing at the globe. (A half-inch section along one side of the front cover has been cut off.) Flaunting their ill-gotten gains, some of the politicians wore coats that evening festooned with solid gold buttons. Despite this gaudy display of wealth, a notice informs the “gentlemen” that they must pay in advance when ordering wine.

The enormous ball supper was supplied by the proprietors of the Sinclair House, a middling hotel on Broadway at East 8th Street. Described in news reports in terms of its vast quantities, such as 30,000 oysters, 1,000 quail, and 500 partridges, the late supper was served between 11 p.m. and 4 a.m. by a small army of stewards and waiters recruited for this occasion.

In the spring of 1871, while planning an elaborate wedding for his daughter, Tweed asked restaurateur Charles Delmonico to “get me up a good dinner for five hundred people.” Although this “simple” meal cost $13,000 ($250,000 in today’s dollars), it was a mere pittance compared to the bridal gifts, which the New York Herald valued at $700,000 ($13+ million). Tweed was arrested later that year and eventually convicted, but his efficient political organization soon rebounded without him.

In the next post, we will pick up the story of Antonio Sivori in June 1872, when he was again running his own establishment, a restaurant named St. Mark’s on 27th Street, only one block up Broadway from the St. James Hotel.

Notes

1. New York Herald, 25 March 1893.

2. New York Times, 26 March 1893.

3. Special thanks to social historian Jan Whitaker for unearthing additional biographical details.

4. King's handbook

3 comments:

I just can't get over how beautiful these menus are, Henry. The Irish menu especially. What a treasure box you found and I am in awe of your detective work to put it all together with Sivori. Bravo!!

This post turned out so well! The canon sculpture is very impressive. I also love to see menus where the costs have been tallied.

Helloo mate nice post

Post a Comment